Australia’s debt and deficit: what this means for growing businesses

Part of running a small business is not only dealing with the internal day to day but also understanding the external factors that shape the economy and where it will go.

The announcement of the Australian federal budget in early October and the State budgets in November once again brought up the issue of the level of debt that Australia will take on as a result of the COVID-19 stimulus and support measures. In this briefing, I’d like to give you some broader perspectives on what Australia’s national debt means and how it might impact our businesses. (Scroll to the bottom for definitions of key terms.)

I know that economics is a dry topic. The reason that I want to discuss this is to ensure that as a business owner you are equipped to make informed decisions about the economy we are all operating in. This kind of information can give you an advantage for making business-critical decisions such as:

• Employing people;

• Financial commitments such as investing in assets, signing leases;

• Growing your business and the pace of growth.

By being informed, you can feel confident to pick up business opportunities and move ahead while your competitors are stuck waiting and seeing because they don’t know what you know.

As a coach and mentor to many businesses through the GFC, the advantage my clients had by being informed about the economy enabled them to be confident in their decisions. Many of those decisions are still delivering rewards for their businesses to this day.

Government Tax Collection and Spending

Firstly, let’s look at the role of government. At the core, the role of federal, state and local government is to collect taxes on behalf of the population and then use that money to deliver the communal services we receive; protection (police and defence), income support (Centrelink), education (kindergarten, primary, secondary and tertiary schooling), and healthcare (Medicare and subsidised medicines).

There are times when a government collects more than it spends (budget surplus) and there are times when a government spends more than it collects (budget deficit). It is the government’s responsibility to even out collections and expenditure over time.

At times like we are in now, when businesses pull back from employing and consumers and businesses pull back from spending, the government has a role to play in filling the void. As we are seeing at the moment, with less tax being collected due to loss of wages and lower company profits, the government has stepped in with programs like JobKeeper and infrastructure spending. Obviously, by spending more money and collecting less tax, the government has to make up the shortfall. There are two ways a government can do this, by either borrowing money or printing it.

Government Borrowing Money

In recent decades the Australian Commonwealth and State governments have borrowed money when their spending has exceeded their tax collections. Everyone can relate to this because at some stage we all have borrowed money to finance an important purchase.

When you borrow money (personally or through your business), the term of the loan is typically for the term of your ability to repay the debt. (For example, home loans are usually capped at 30 years because that’s generally the term of the borrower’s working life.)

It’s very different when a country borrows money because it has the capability to generate income for hundreds of years to repay its debts. And for a nation like Australia, its income earning capacity is practically unlimited. Nations can also give themselves pay rises whenever they need by increasing taxes. (That also has pros and cons for the economy, which I won’t go into here.)

Responsible governments borrow money for important assets – for example, building new roads or hospitals that will deliver benefits for many years.

In response to COVID-19, we are seeing governments borrow money to finance programs like JobKeeper, which we know has saved many people from losing their jobs (and the long-term pain of unemployment) and loss of tax revenue that comes with this. The challenge comes when the interest from the national debt starts to form a sizable amount in comparison to the revenue the government collects.

The government borrows money by selling government bonds, which are effectively a promise to pay back the bond price plus regular interest. Organisations that buy government bonds (and in doing so are effectively the lenders) are typically large institutional investors such as banks, who then sell the bonds on to other investors that need to hold some assets that can be easily converted to cash. For example, large insurance companies and superannuation funds need to have money readily available for redemptions (insurance pay-outs and super withdrawals), so they can’t have all their funds tied up in property and share related investments, which makes bonds a good option.

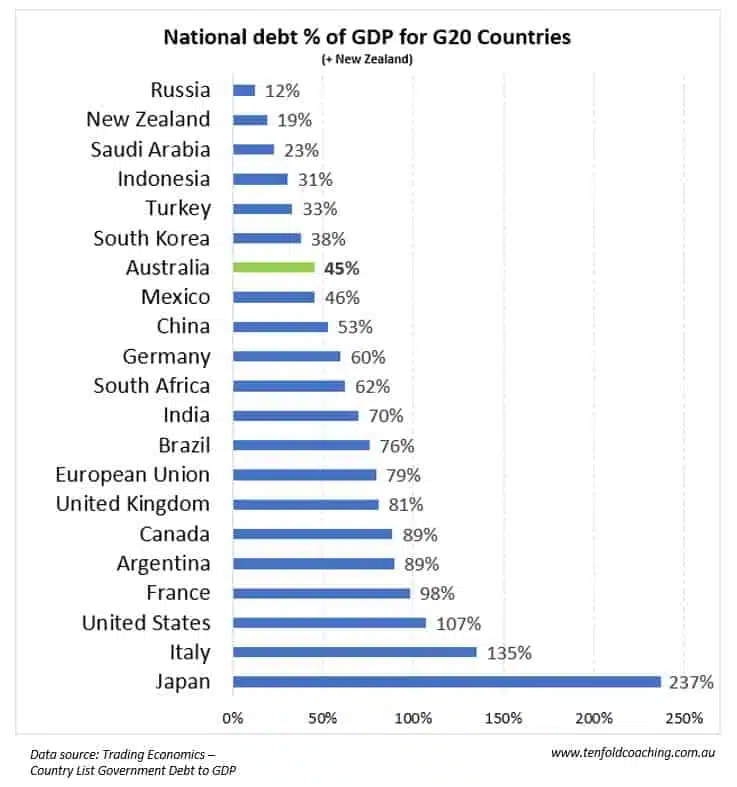

As you can see from the chart, Australia’s national debt as a percentage of GDP is among the lowest of the G20 countries.

Printing Money

The other option available to governments is to create money; this is often referred to as ‘printing money’ or the technical term of quantitative easing (QE). As the term ‘printing money’ implies, the government effectively creates money out of thin air and as a result they have more money to spend. (In the old days, the bank would physically print money. Now it’s done digitally by adding more dollars to the bank account of the Reserve Bank of Australia (the RBA). The RBA uses that extra money to buy the government bonds back from the institutional investors, thereby pumping money into the economy.

The federal government can do this because, through the Reserve Bank, they control the currency and the money supply.

It sounds too good to be true, and so as you’d expect there is a downside. When the government prints money, it can cause inflation which means prices go up and the money we currently have is worth a little bit less. It also means that if the Australian government prints money then the buying power of the Australian dollar decreases versus another country’s currency where they haven’t printed money. The extreme example of where printing money goes awry is Zimbabwe, where inflation is running at over 500% per annum – the price of items is increasing by 5 times over the year.

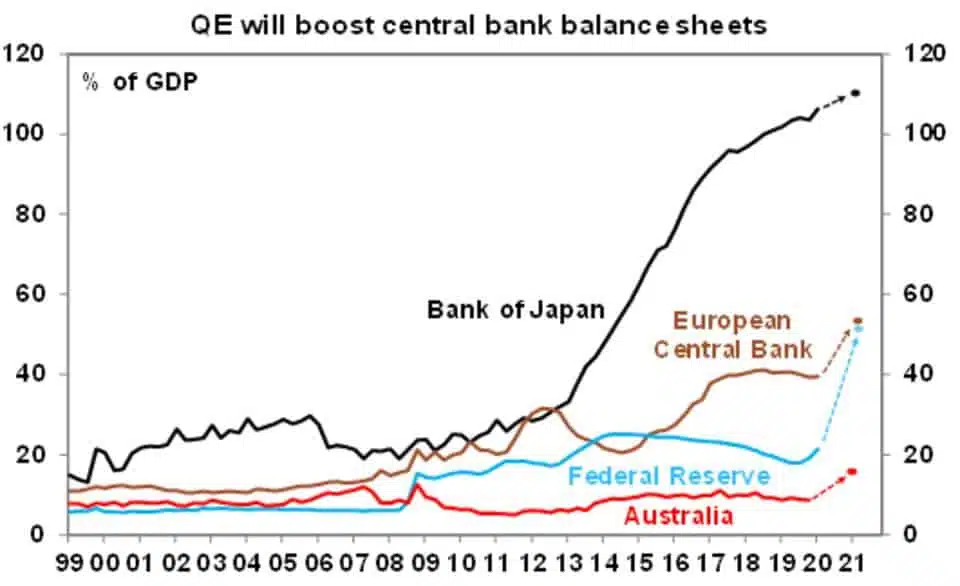

This year the Australian government has both borrowed and printed money. However, as you can see from the graph, our level of money printing (QE) and our level of overall debt as a percentage of GDP is low compared to the Bank of Japan, European Central Bank, and the US Federal Reserve.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

How does the national debt and deficit impact my small business?

So, while we hear about record levels of government debt and the Australian government printing money, we are doing so at a much lower level than other countries. Another positive in our favour is that interest rates are lower than they’ve ever been in Australia, which means the repayments on the national debt are very manageable in the short and medium term.

As Australia pays for all of the spending that has been promised (or we face a third wave of COVID-19 and/or another recession), Australia is in a much better position to borrow and print money than many other nations. You can be assured that we have the best opportunity to rebound from 2020 and get our economy back on track.

I hope this briefing helps you to feel confident as you consider the future of your business and the growth opportunities available to you.

Ash

——————————

Key terms:

Budget surplus: when the government’s income (through collecting tax) exceeds its expenditure. More money coming in than going out.

Budget deficit: when the government’s expenditure exceeds its income. More money going out than coming in.

Debt: The amount the government owes.

Inflation: The rate at which the cost of goods and services increase.

GDP: Gross Domestic Product refers to the total amount of goods and services produced by a country.

Ash

Ashley Thomson B.Eng(Hons), Grad. Dip. Mgmt, MEI

Managing Director

Tenfold Business Coaching

———————————